I wrote this on April 12th, 2019. Its message is still relevant.

On March 28th, the Chronicle of Higher Education published Karin Fischer’s article titled: “How International Education’s Global Era Lost its Sheen.” As someone just dipping her toes into the field, this news felt disappointing. I work at a small college where it will already take some time to develop an understanding of the benefits a study abroad experience amongst the student population, but I am hoping I could get the support of our leadership team to drive these efforts. While the evidence that studying abroad has not disappeared – the benefits of internalization are certainly not what’s in dispute – I fear for the influence these perceived “market” trends might have on our study abroad programming. This comes at a time when I feel particularly worn by the amount of work that lies before me.

At first, the article put a momentary damper on my ambitious goals for students’ study abroad opportunities at Menlo College. Fischer does suggest in the article that there will now be a “decline” after all, and our society doesn’t particularly like or favor “declines” in things we desire for our world.

But the descent from the “peak” in a global era certainly is not a fault of the research behind the benefits of internationalization, it is all political.

First, as the article mentions, the current Administration directing policy in the United States is absolutely contributing to a decline in international student enrollment in US universities. There are plenty of articles about this. Of course, after two years of Trump’s immigration policies we are seeing this decline. Fischer mentions it all the time in her weekly newsletter, Latitudes.

The second factor is far more interesting to me: the “internal critique” of internationalization coming from higher education. The Chronicle’s article highlights NYU in particular, and as NYU is my alma mater, I have quite a number of thoughts on the issue, all related to the “internal critique”.

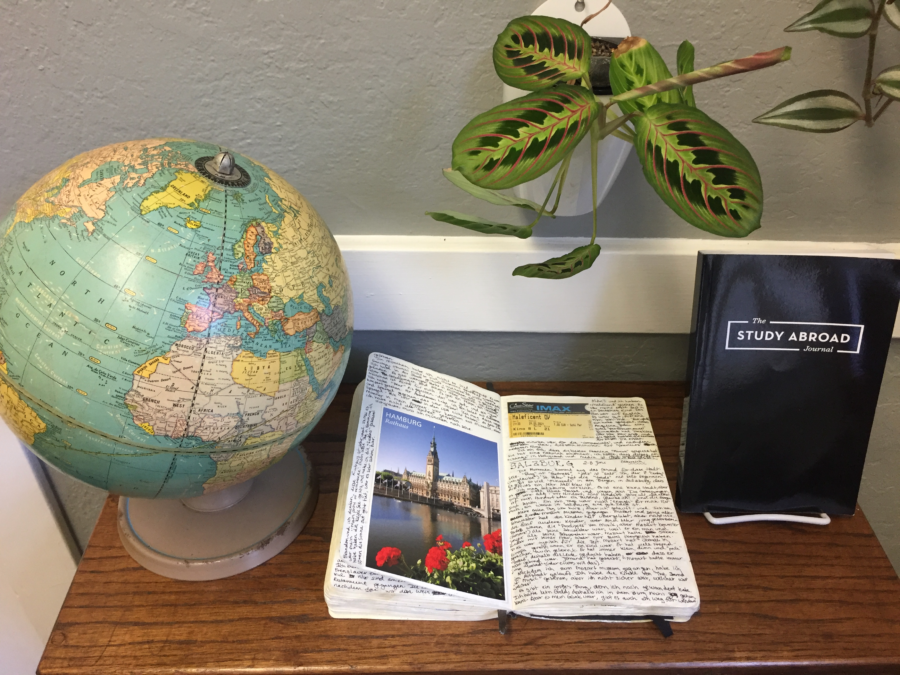

The most impactful course I took at NYU was “Sociology of the Internationalization of Higher Education” at NYU Berlin. This course was taught by Professor Reinhard Isensee, a professor for NYU Berlin and Humboldt Universität. The course was also offered at Humboldt, allowing NYU and Humboldt students to engage in class discussion together for a part of the course (US and German academic calendars do not align perfectly for the full course to be combined). To make things more interesting, about half of the NYU students in the class studied full-time at NYU Abu Dhabi. Essentially, we had students accustomed to the German system, the US system, and students with what is still a rather unique experience – completing a degree at an American university in a foreign country.

We all began to question the system of higher education in that class, particularly the US system, and NYU’s global model within that system. At that time, the students who completed their degrees in Abu Dhabi did not have to take Arabic. They stuck primarily to the campus. NYU Abu Dhabi was not integrated into Abu Dhabi itself. I do not know if this has changed much in the last five years. I was at NYU when there was a vote of no confidence for former President John Sexton, and I was there when the labor issues in creating NYU Abu Dhabi’s new campus emerged, as well as to hear about the professor who was banned from entering the country after he had been conducting research on this issue.

I myself was, and still am, a critic of the programming at NYU Berlin. A number of administrators there I consider my friends, and I visit the academic center whenever I return to Berlin. But I spoke out about the fact that students were living with their NYU classmates rather than with host families or other German students. I advocated against making the process to live off-campus so difficult, which was not the fault of NYU Berlin administration, but rather at the demands of “the Mothership” (as one of my friends jokingly called NYU administration in New York).

If the fast development of this kind of study abroad is slowing down, I see it as a good thing. I think that we all in higher education need to take a step back and evaluate what study abroad is. Is the drastic slash in Language programs truly beneficial to our goals as a society? While the administration may seem to be leaning in that direction, we in higher education have some choices to make. (Or have we already, if over 600 language programs are gone?)

I hope to sit down with the leadership at Menlo College and promote the importance of learning languages and studying abroad. Even if our country becomes more “isolationist” in economic policy, that may mean that it is up to our future diplomats, business leaders, and international educators to cultivate relationships with other countries. But I don’t think the plans of our administration are going to last very long. When countries don’t work together, they do the opposite: they fight. And someone conquers.